An Example of using the PEWMA model for data analysis

In Brandt and Williams (1999)

we present an application of the basic PEWMA model. This model is

a state-space model

that is estimated using the Kalman filter. The basic model can be

written in two equations: an observation or measurement

equation and a state or stochatic equation. The basic model is

Pr(yt |mt) = mtyt exp(mt) / yt !

where

mt = mt-1exp(rt)nt.

This model can be used to describe persistent, or long memoried event counts series. For details see Brandt et al. 2000.

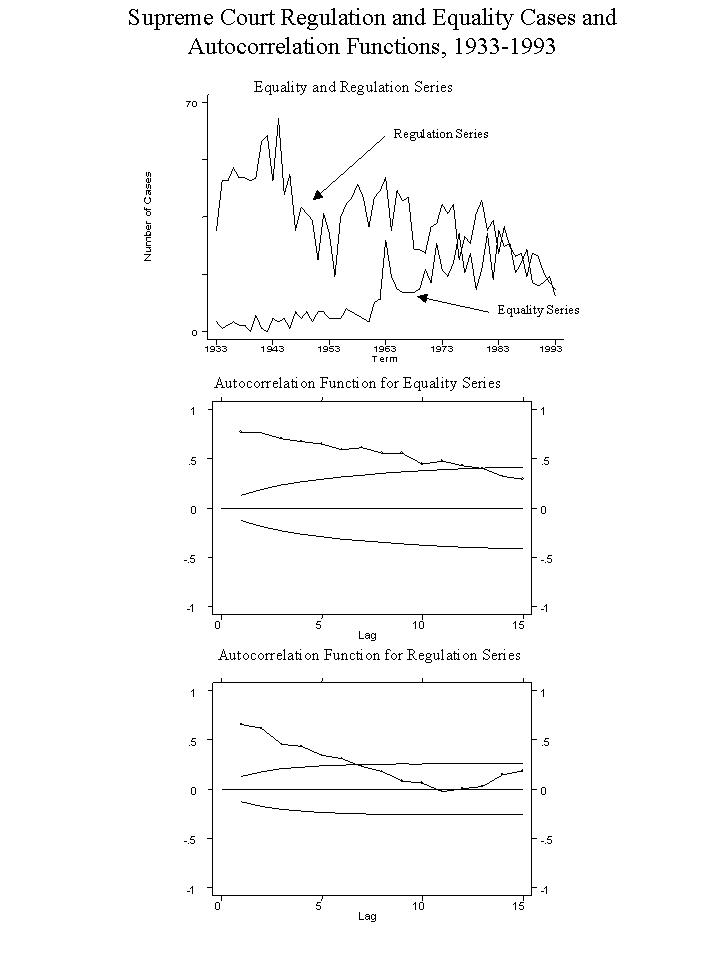

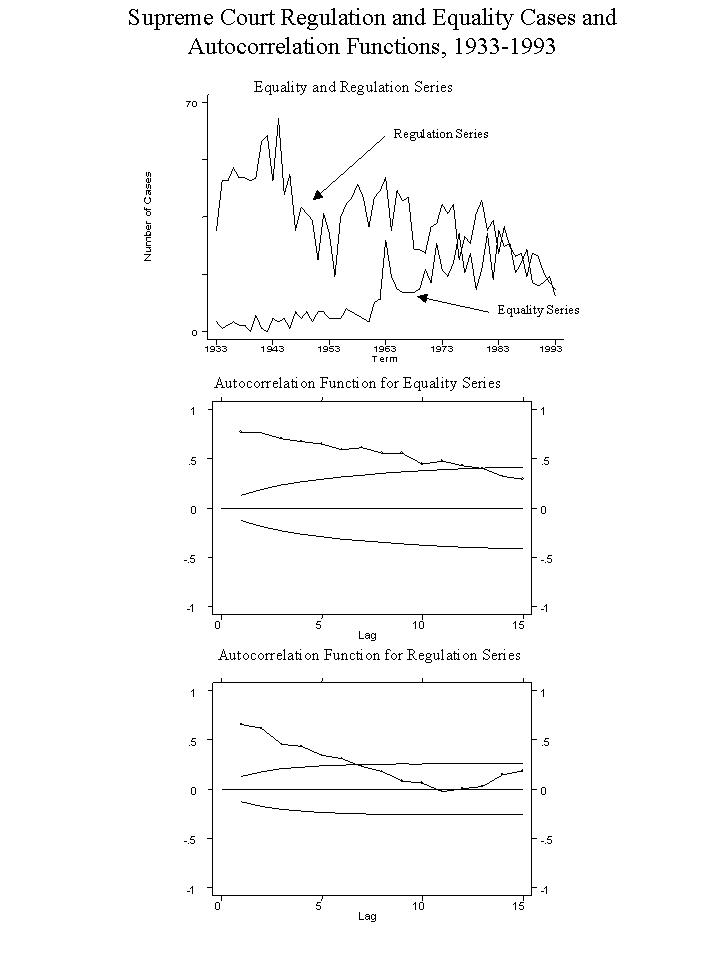

An emerging area of scholarship on the Supreme Court looks at

the nature of agenda change over time. Changes in the Court's

agenda may result from new membership, landmark decisions,

leadership changes, and a new role for the institution. Of great

interest is the nature of the dynamic process that accompanies

agenda change.

Pacelle (1991) and Pacelle et al. (1998) argue that significant

agenda change occurred in two main areas of the Court's agenda

since the 1950s. First, there was a significant increase in the

number of cases concerning issues of Equality and the 14th

Amendment (e.g. race, gender, age, disability). Second, there was

a decrease in the number of cases involving Regulation (e.g. the

regulation of business by the federal government). These changes

in agenda composition and dynamics resulted from three major

changes in the Court. The first was the shift to civil rights and

civil liberties issues in the wake of the civil rights movement

and the Court's decision to abandon efforts to interfere in

regulatory policy after Justice Harlan Stone's famous Footnote

Four in U.S. v. Carolene Products. More significantly in

1953, the appointment of Earl Warren as Chief Justice altered the

leadership of the Court. Warren's leadership is viewed as a

significant change from that of his predecessor Fred Vinson.

Finally, the Court delivered the landmark decision in Brown

v. Board of Education during the 1953 term.

In our replication, we utilize the number of cases in the

Equality and Regulation agenda areas to which the U.S. was a

party from 1933 to 1993. Using the counts of the number of cases

is preferred because the percentages are influenced by the number

of cases that the Court accepts in all areas. The more cases the

Court accepts in other areas, the less certain we can be of the

changes, since they will affect the denominator in the

calculation of the proportion. Thus the actual counts of the

cases in each area present a better measure of the agenda.

Based on this data, we are interested in determining the changes

in the Court's agenda after the 1953 term. Our expectation is

that in the post-1953 period, we should see a rise in the number

of cases dealing with issues of Equality (racial, gender, etc.)

and a decline in the number of cases dealing with economic

Regulation. For our analysis we perform an intervention analysis

of the number of cases in the economic Regulation and Equality

agendas before and after 1953.

Each of these series exhibits a strong degree of temporal

dependence, as seen by looking at the data and its ACFs:

Based on these persistent ACF's, we estimated a

series of intervention models (again, for details, see Brandt and

Williams 1998).

Of interest is whether the decline begins in 1953 for the

Regulation cases and whether the rise in Equality cases begins

immediately after Brown or whether there was a lag. Of

additional interest is the year in which the lag intervention

occurred. The temporary intervention is used because we believe

its effect raises the number of cases in the Equality series

(decreases the number of cases in the Regulation series). Such

temporary effects, however, should have a permanent effect on the

level of the series (see Harvey 1991: 397-99). Since we are not

sure of the lag specification for the intervention (i.e. how long

after Brown the increase/decrease in cases occurred), we

empirically determined the intervention specifications from a one

period to an 10 period forward lag (1954-1963). The optimal

intervention specification will maximize the log-likelihood of

the model.

Using the PEWMA, the lag specification with the highest

likelihood value for the series was 10 lags for the Equality

series (1963) and one lag for the Regulation series (1954). These

are consistent with the VAR results reported in Pacelle et al.

(1998). The coefficient in the PEWMA model for the intervention

was 0.9024 for the Equality series and -0.7165 for the economic

Regulation series. In the Regulation case the intervention has a

negative effect as predicted and a large absolute t-ratio greater

than three. For the equality series, a similar conclusion holds.

PEWMA estimates for equality series

with interventions

| Year | Omega | I(t) | Log-Likelihood | AIC |

| 1953 | 0.568 | -0.231 | -168.07 | 338.14 |

| 1954 | 0.570 | -0.234 | -168.00 | 338.00 |

| 1955 | 0.570 | -0.303 | -168.00 | 338.00 |

| 1956 | 0.564 | 0.302 | -167.95 | 337.89 |

| 1957 | 0.566 | 0.057 | -168.15 | 338.30 |

| 1958 | 0.573 | -0.204 | -168.07 | 338.14 |

| 1959 | 0.586 | -0.556 | -167.58 | 337.16 |

| 1960 | 0.594 | -1.053 | -166.16 | 334.32 |

| 1961 | 0.568 | -0.113 | -168.11 | 338.22 |

| 1962 | 0.559 | -0.281 | -167.83 | 337.65 |

| 1963 | 0.628 | 0.902 | -162.14 | 326.28 |

| 1964 | 0.575 | 0.160 | -168.01 | 338.03 |

PEWMA estimates for economic regulation

series with interventions

| Year | Omega | I(t) | Log-Likelihood | AIC |

| 1953 | 0.581 | -0.033 | -205.93 | 413.86 |

| 1954 | 0.608 | -0.717 | -201.55 | 405.09 |

| 1955 | 0.578 | 0.060 | -205.89 | 413.79 |

| 1956 | 0.580 | 0.100 | -205.81 | 413.62 |

| 1957 | 0.582 | 0.090 | -205.82 | 413.65 |

| 1958 | 0.585 | 0.176 | -205.47 | 413.93 |

Using the AIC criteria, we chose the model with a 10 period lead for the equality series, and a one period lead for the economic regulation series. It therefore appears that the change in the Supreme Court case agenda for civil rights was delayed, while the change in the regulation case agenda was rather proximate to the 1953 Supreme Court term.